Music with Ease > 19th Century Italian Opera > Cavalleria Rusticana (Mascagni) - Synopsis

Cavalleria Rusticana -

Synopsis

(English title: Rustic Chivalry)

An Opera by Pietro Mascagni

CHARACTERS

TURIDDU, a young soldier………………………….. Tenor

ALFIO, the village teamster…………………………. Baritone

LOLA, his wife……………………………………… Mezzo-soprano

MAMMA LUCIA, Turiddu’s mother………………. Contralto

SANTUZZA, a village girl…………………………. Soprano

Villagers, peasants, boys.

Time: The present, on Easter day.

Place: A village in Sicily.

"Cavalleria Rusticana" in its original form is a short story, compact and tense, by Giovanni Verga. From it was made the stage tragedy, in which Eleonora Duse displayed her great powers as an actress. It is a drama of swift action and intense emotion; of passion, betrayal, and retribution. Much has been made of the role played by the "book" in contributing to the success of the opera. It is a first-rate libretto -- one of the best ever put forth. It inspired the composer to what so far has remained his only significant achievement. But only in that respect is it responsible for the success of "Cavalleria Rusticana" as an opera. The hot blood of the story courses through the music of Mascagni, who in his score also has quieter passages, that make the cries of passion the more poignant. Like practically every enduring success, that of "Cavalleria Rusticana" rests upon merit. From beginning to end it is an inspiration. In it, in 1890, Mascagni at the age of twenty-one, "found himself," and ever since has been trying, unsuccessfully, to find himself again.

The prelude contains three passages of significance in the development of the story. The first of these is the phrase of the despairing Santuzza, in which she cries out to Turiddu that, despite his betrayal and desertion of her, she still loves and pardons him. The second is the melody of the duet between Santuzza and Turiddu, in which she implores him to remain with her and not to follow Lola into the church. The third is the air in Sicilian style, the "Siciliano," which, as part of the prelude, Turridu sings behind the curtain, in the manner of a serenade to Lola, "O Lola, bianca come fior di spino" (O Lola, fair as a smiling flower).

With the end of the "Siciliano" the curtain rises. It discloses a public square in a Sicilian village. On one side, in the background, is a church, on the other Mamma Lucia’s wineship and dwelling. It is Easter morning. Peasants, men, women, and children cross or move about the stage. The church bells ring, the church doors swing open, people enter. A chorus, in which, mingled with gladness over the mild beauty of the day, there also is the lilt of religious ecstasy, follows. Like a refrain the women voice and repeat "Gli aranci olezzano sui verdi margini" (Sweet is the air with the blossoms of oranges). They intone "La Virgine serena allietasi del Salvator" (The Holy Mother mild, in ecstasy fondles the child), and sing of "Tempo e si momori," etc. (Murmurs of tender song tell of a joyful world). The men, meanwhile, pay a tribute to the industry and charm of woman. Those who have not entered the church, go off singing. Their voices die away in the distance.

Santuzza, sad of mien, approaches Mamma Lucia’s house, just as her false lover’s mother comes out. There is a brief colloquy between the two women. Santuzza asks for Turiddu. His mother answers that he has gone to Francofonte to fetch some wine. Santuzza tells her that he was seen during the night in the village. The girl’s evident distress touches Mamma Lucia. She bids her enter the house.

"I may not step across your threshold," exclaim Santuzza. "I cannot pass it, I, most unhappy outcast! Excommunicated!"

Mamma Lucia may have her suspicions of Santuzza’s plight. "What of my son?" she asks. "What have you to tell me?"

But at that moment the cracking of a whip and the jingling of bells are heard from off stage. Alfio, the teamster, comes upon the scene. He is accompanied by the villagers. Cheerfully he sings the praises of a teamster’s life, also of Lola's, his wife’s beauty. The villagers join him in chorus. "I1 cavallo scalpita" (Gayly moves the tramping horse).

Alfio asks Mamma Lucia if she still has on hand some of her fine old wine. She tells him it has given out. Turiddu has gone away to buy a fresh supply of it.

"No," says Alfio. "He is here. I saw him this morning standing not far from my cottage."

Mamma Lucia is about to express great surprise. Santuzza is quick to check her.

Alfio goes his way. A choir in the church intones the "Regina Coeli." The people in the square join in the "Allelujas." Then they kneel and, led by Santuzza’s voice, sing the Resurrection hymn, "Innegiamo, il Signor non e morto" (Let us sing of the Lord now victorious). The "Allelujas" resound in the church, which all, save Mamma Lucia and Santuzza, enter.

Mamma Lucia asks the girl why she signaled her to remain silent when Alfio spoke of Turiddu’s presence in the village. "Voi lo sapete" (Now you shall know), exclaims Santuzza, and in one of the most impassioned numbers of the score, pours into the ears of her lover’s mother the story of her betrayal. Before Turiddu left to serve his time in the army, he and Lola were in love with each other. But, tiring of awaiting his return, the fickle Lola married Alfio. Turiddu, after he had come back, made love to Santuzza and betrayed her now, lured by Lola, he has taken advantage of Alfio’s frequent absences, and has gone back to his first love. Mamma Lucia pities the girl, who begs that she go into church and pray for her.

Turiddu comes, a handsome fellow. Santuzza upbraids him for pretending to have gone away, when instead he has surreptitiously been visiting Lola. It is a scene of vehemence. But when Turiddu intimates that his life would be in danger were Alfio to know of his visits to Lola, the girl is terrified. "Battimi, insultami, t’amo e perdono" (Beat me, insult me, I still love and forgive you).

Such is her mood -- despairing, yet relenting. But Lola’s voice is heard off stage. Her song is carefree, a key to her character, which is fickle and selfish, with a touch of the cruel. "Fior di giaggiolo" (Bright flower, so glowing) runs her song. Heard off stage, it yet conveys in its melody, its pauses, and inflections, a quick sketch in music of the heartless coquette, who, to gratify a whim, has stolen Turiddu from Santuzza. She mocks the girl, then enters the church. Only a few minutes has she been on the stage, but Mascagni has let us know all about her.

A highly dramatic scene, one of the most impassioned outbursts of the score, occurs at this point. Turiddu turns to follow Lola into the church. Santuzza begs him to stay. "No, no, Turiddu, rimani, rimani, ancora-Abbandonarmi dunque tu vuoi?" (No, no, Turiddu! Remain with me now and forever! Love me again! How can you forsake me?).

A highly dramatic phrases, already heard in prelude, occurs at "La tua Santuzza piange t’implora (Lo! here thy Santuzza, weeping, implores thee).

Turiddu repulses her. She clings to him. He loosens her hold and casts her from to the ground. When she rises, he has followed Lola into the church.

But the avenger is nigh. Before Santuzza has time to think, Alfio comes upon the scene. He is looking for Lola. To him in the fewest possible words, and in the white voice of suppressed passion, Santuzza tells him that his wife has been unfaithfully with Turiddu. In the brevity of its recitatives, the tense summing up in melody of each dramatic situation as it develops in the inexorably swift unfolding of the tragic story, lies the strength of "Cavalleria Rusticana."

Santuzza and Alfio leave. The square is empty. But the action goes on in the orchestra. For the intermezzo -- the famous intermezzo -- which follows, recapitulates, in its forty-eight bars, what has gone before, and foreshadows the tragedy that is impending. There is no restating here of leading motives. The effect is accomplished by means of terse, vibrant melodic progression. It is melody and yet it is drama. Therein lies its merit. For no piece of serious music can achieve the world-wide popularity of this intermezzo and not possess merit.

Mr. Krehbiel, in A Second Book of Operas, gives an instance of its unexampled appeal to the multitude. A burlesque on this opera was staged in Vienna. The author of the burlesque thought it would be a great joke to have the intermezzo played on a hand-organ. Up to that point the audience had been hilarious. But with the first wheezy tone of the grinder the people settled down to silent attention, and, when the end came, burst into applause. Even the hand-organ could not rob the intermezzo of its charm for the public!

What is to follow in the opera is quickly accomplished. The people come out of church. Turiddu, in high spirits, because he is with Lola and because Santuzza no longer is hanging around to reproach him, invites his friends over to his mother’s wineshop. Their glasses are filled. Turiddu dashes off a drinking song, "Viva, I vivo spumeggiante" (Hail! The ruby wine now flowing).

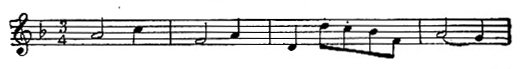

Here is the theme of this song:

[Music excerpt]

Alfio joins them. Turiddu offers him wine. He refuses it. The women leave, taking Lola with them. In a brief exchange of words Alfio gives the challenge. In Sicilian fashion the two men embrace, and Turiddu, in token of acceptance, bites Alfio’s ear. Alfio goes off in the direction of the place where they are to test their skill with the stiletto.

Turiddu calls for Mamma Lucia. He is going away, he tells her. At home the wine cup passes too freely. He must leave. If he should not come back she must be like a kindly mother to Santuzza -- "Santa, whom I have promised to lead to the altar."

"Un bacio, mamma! Un alto bacio! -- Addio!" (One kiss, one kiss, my mother. And yet another. Farewell!)

He goes. Mamma Lucia wanders aimlessly to the back of the stage. She is weeping. Santuzza comes on, throws her arms around the poor woman’s neck. People crowd upon the scene. All is suppressed excitement. There is a murmur of distant voices. A woman is heard calling from afar: "They have murdered neighbour Turiddu!"

Several women enter hastily. One of them, the one whose voice was heard in the distance, repeats, but now in a shriek, "Hammo ammazzato compre compare Turiddu!"- (They have murdered neighbour Turiddu!).

Santuzza falls in a swoon. The fainting form of Mamma Lucia is supported by some of the women.

"Cala rapidamente la tela" (The curtain falls rapidly).

A tragedy of Sicily, hot in the blood, is over.

When "Cavalleria Rusticana" was produced, no Italian opera had achieved such a triumph since "Aida" -- a period to nearly twenty years. It was hoped that Mascagni would prove to be Verdi’s successor, a hope which, needless to say, has not been fulfilled.

To "Cavalleria Rusticana," however, we owe the succession of short operas, usually founded on debased and sordid material, in which other composers have paid Mascagni the doubtful compliments of imitation in hopes of achieving similar success. Of all these, "Pagliacci," by Leoncavallo, is the only one that has shared the vogue of the Mascagni opera. The two make a remarkably effective double bill.

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-23 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |