Music with Ease > Operas of Richard Wagner > Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (Wagner) - Synopsis

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg - Synopsis

(English title: The Mastersingers of Nuremberg)

An Opera by Richard Wagner

CHARACTERS

Mastersingers:

HANS SACHS, Cobbler ………….….….….….….…. Bass

VEIT POGNER, Goldsmith ………….….….….….…. Bass

KUNZ VOGELGESANG, Furrier ………….….….…. Tenor

CONRAD NACHTIGALL, Buckle-Maker ………….…. Bass

SIXTUS BECKMESSER, Town Clerk ………….….…. Bass

FRITZ KOTHNER, Baker ………….….….….….….…. Bass

BALTHAZAR ZORN, Pewterer ...................….….….…. Tenor

ULRICH EISLINGER, Grocer ………….….….….….…. Tenor

AUGUST MOSER, Tailor …………….….….….….…. Tenor

HERMANN ORTEL, Soap-boiler ………….….….….… Bass

HANS SCHWARZ, Stocking-Weaver ………….….…. Bass

HANS FOLZ, Coppersmith ………….….….….….….…. Bass

Other Characters:

WALTHER VON STOLZING, a young Franconian knight….. Tenor

DAVID, apprentice to HANS SACHS……………………….. Tenor

A NIGHT WATCHMAN…………………………………….... Bass

EVA, daughter of POGNER…………………………………. Soprano

MAGDALENA, EVA’S nurse………………………………... Mezzo-Soprano

Burghers of the Guilds, Journeymen, ‘Prentices, Girls, and Populace.

Time: Middle of the Sixteenth Century.

Place: Nuremburg.

Eugen Gura in the role of Hans Sachs in Wagner's opera, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

Wagner’s music-dramas are all unmistakably Wagner, yet they are wonderfully varied. The style of the music in each adapts itself plastically to the character of the story. can one, for instance, imagine the music of "Tristan" wedded to the story of "The Mastersingers," or vice versa? A tragic passion, inflamed by the arts of sorcery inspired the former. The latter is a thoroughly human tale set to thoroughly human music. Indeed, while "Tristan" and "The Ring of the Nibelung" are tragic, and "Parsifal" is deeply religious, "The Mastersingers" is a comic work, even bordering in one scene on farce. Like Shakespeare, Wagner was equally at home in tragedy and comedy.

Walthur von Stolzing is in love with Eva. Her father having promised her to the singer to whom at the coming midsummer festival the Mastersingers shall adjudge the prize, it becomes necessary for Walther to seek admission to their art union. He is, however, rejected, his song violating the rules to which the Mastersingers slavishly adhere. Beckmesser is also instrumental in securing Walther’s rejection. The town clerk is the "marker" of the union. His duty is to mark all violations of the rules against a candidate. Beckmesser, being a suitor for Eva’s hand, naturally makes the most of every chance to put down a mark against Walther.

Sachs alone among the Mastersingers has recognized the beauty of Walther’s song. Its very freedom from rule and rote charms him, and he discovers in the young knight’s untrammeled genius the power which, if properly directed, will lead art from the beaten path of tradition toward a new and loftier ideal.

After Walther’s failure before the Mastersingers the impetuous young knight persuades Eva to elope with him. But at night as they are preparing to escape, Beckmesser comes upon the scene to serenade Eva. Sachs, whose house is opposite Pogner’s, has meanwhile brought his work bench out into the street and insists on "marking" what he considers Beckmesser’s mistakes by bringing his hammer down upon his last with a resounding whack. The louder Beckmesser sings the louder Sachs whacks. Finally the neighbours are aroused. David, who is in love with Magdalena and thinks Beckmesser is serenading her, falls upon him with a cudgel. The whole neighbourhood turns out and a general melée ensues, during which Sachs separates Eva and Walther and draws the latter into his home.

The following morning Walther sings to Sachs a song which has come to him in a dream, Sachs transcribing the words and passing friendly criticism upon them and the music. The midsummer festival is to take place that afternoon, and through a ruse Sachs manages to get Walther’s poem into Beckmesser’s possession, who thinking the words are by the popular cobbler-poet, feels sure he will be the chosen master. Eva, coming into the workshop to have her shoes fitted, finds Walther, and the lovers depart with Sachs, David, and Magdalena for the festival. Here Beckmesser, as Sachs had anticipated, makes a wretched failure, as he has utterly missed the spirit of the poem, and Walther, being called upon by Sachs to reveal its beauty in music, sings his prize song, winning at once the approbation of the Mastersingers and the populace. He is received into their art union and at the same time wins Eva as his bride.

The chorus in Act I of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg as performed in 1960 at the Leipzig Opernhaus. (Source: Bundesarchiv.)

The Mastersingers were of burgher extraction. They flourished in Germany, chiefly in the imperial cities, during the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries. They did much to generate and preserve a love of art among the middle classes. Their musical competitions were judged according to a code of rules which distinguished by particular names thirty-two faults to be avoided. Scriptural or devotional subjects were usually selected and the judges or Merker (markers) were, in Nuremburg, four in number, the first comparing the words with the Biblical text, the second criticizing the prosody, the third the rhymes, and the fourth the tune. He who had the fewest marks against him received the prize.

Hans Sachs, the most famous of the Mastersingers, born November 5, 1494, died January, 1576, in Nuremburg, is said to have been the author of some six thousand poems. He was a cobbler by trade --

Hans Sachs was a shoe-

Maker and poet too.

A monument was erected to him in the city of his birth in 1874.

"The Mastersingers" is a simple, human love story, simply told, with many touches of humour to enliven it, and its interest enhanced by highly picturesque, historical surroundings. As a drama it conveys also a perfect picture of the life and customs of Nuremburg of the time in which the story plays. Wagner must have made careful historical researches, but his book lore is not thrust upon us. The work is so spontaneous that the method and manner of its art are lost sight of in admiration of the result. Hans Sachs himself could not have left a more faithful portrait of life in Nuremburg in the middle of the sixteenth century.

"The Mastersingers" has a peculiarly Wagnerian interest. It is Wagner’s protest against the narrow-minded critics and the prejudiced public who so long refused him recognition. Edward Hanslick, the bitterest of Wagner’s critics, regarded the libretto as a personal insult to himself. Being present by invitation at a private reading of the libretto, which Wagner gave in Vienna, Hanslick rose abruptly and left after the first act. Walther von Stolzing is the incarnation of new aspirations in art; the champion of a new art ideal, and continually chafing under the restraints imposed by traditional rules and methods. Hans Sachs is a conservative. But, while preserving what is best in art traditions, he is able to recognize the beautiful in what is new. He represents enlightened public opinion. Beckmesser and the other Mastersingers are the embodiment of rank prejudice-the critics. Walther’s triumph is also Wagner’s. Few of Wagner’s dramatic creations equal in life-like interest the character of Sachs. It is drawn with a strong, firm hand, and filled in with many delicate touches.

The Vorspiel (Preface) gives a complete musical epitome of the story. It is full of life and action -- pompous impassioned, and jocose in turn, and without a suggestion of the over-wrought or morbid. Its sentiment and its fun are purely human. In its technical construction it has long been recognized as a masterpiece.

In the sense that it precedes the rise of the curtain, this orchestral composition is a Vorspiel, or prelude. As a work, however, it is a full-fledged overture, rich in thematic material. These themes are Leading Motives heard many times, and in wonderful variety in the three acts of "The Mastersigners."

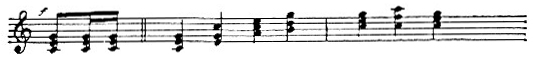

The pompous Motive of the Mastersingers opens the Vorspiel. This theme gives capital musical expression to the characteristics of these dignitaries; eminently worthy but self-sufficient citizens who are slow to receive new impressions and do not take kindly to innovations. Our term of old fogy describes them imperfectly, as it does not allow for their many excellent qualities. They are slow to act, but if they are once aroused their ponderous influence bears down all opposition. At first an obstacle to genuine reform, they are in the end the force which pushes it to success. Thus there is in the Motive of the Mastersingers a certain ponderous dignity which well emphasizes the idea of conservative power.

In great contrast to this is the Lyric Motive, which seems to express the striving after a poetic ideal untrammeled by old-fashioned restrictions, such as the rules of the Mastersingers impose.

But, the sturdy conservative forces are still unwilling to be persuaded of the worth of this new ideal. Hence the Lyric Motive is suddenly checked by the sonorous measures of the Mastersingers’ March.

In this the majesty of law and order finds expression. It is followed by a phrase of noble breadth and beauty, obviously developed from portions of the Motive of the Mastersingers, and so typical of the goodwill which should exist among the members of a fraternity that it may be called the Motive of the Art Brotherhood.

It reaches an eloquent climax in the Motive of the Ideal.

Opposed, however, to this guild of conservative masters is the restless spirit of progress. Hence, though stately the strains of the Mastersingers’ March and of the Guild Motive, soon yield to a theme full of emotional energy and much like the Lyric Motive. Walther is the champion of this new ideal -- not, however, from a purely artistic impulse, but rather through his love for Eva. Being ignorant of the rules and rote of the Mastersingers he sings, when he presents himself for admission to the fraternity, measures which soar untrammeled into realms of beauty beyond the imagination of the masters. But it was his love for Eva which impelled him to seek admission to the brotherhood, and love inspired his song. He is therefore a reformer only by accident; it is not his love of art, but his passion for Eva, which really brings about through his prize song a great musical reform. This is one of Wagner’s finest dramatic touches -- the love story is the mainspring of the action, the moral is pointed only incidentally. Hence all the motives in which the restless striving after a new ideal, or the struggles of a new art form to break through the barriers of conservative prejudice, find expression, are so many love motives, Eva being the incarnation of Walther’s ideal. Therefore the motive which breaks in upon the Mastersingers’ March and Guild Motive with such emotional energy expresses Walther’s desire to possess Eva, more than his yearning for a new ideal in art. So I call it the Motive of Longing.

A portion of "Walther’s Prize Song," like a swiftly

whispered declaration of love, leads to a variation of one of the most beautiful themes of the work-the Motive of Spring.

And now Wagner has a fling at the old fogyism which was so long as obstacle to his success. He holds the masters up to ridicule in a delightfully humorous passage which parodies the Mastersingers’ and Art Brothrhood motives, while the Spring Motive vainly strives to assert itself. In the bass, the following quotation is the Motive of Ridicule, the treble being a variant of the Art Brotherhood Motive.

When it is considered that the opposition Wagner encountered from prejudiced critics, not to mention a prejudiced public, was the bane of his career, it seems wonderful that he should have been content to protest against it with this pleasant raillery instead of with bitter invective. The passage is followed by the Motive of the Mastersingers, which in turn leads to an imposing combination of phrases. We hear the portion of the Prize Song, already quoted -- the Motive of the Mastersigners as bass -- and in the middle voices portions of the Mastersingers’ March; a little later the Motive of the Art Brotherhood and the Motive of Ridicule are added, this grand massing of orchestral forces reaching a powerful climax, with the Motive of the Ideal, while the Motive of the Mastersingers brings the Vorspiel to a fitting close. In this noble passage, in which the "Prize Song" soars above the various themes typical of the masters, the new ideal seems to be borne to its triumph upon the shoulders of the conservative forces which, won over at last, have espoused its cause with all their sturdy energy.

This concluding passage in the Vorspiel thus brings out with great eloquence the inner significance of "Die Meistersinger." In whatever the great author and composer of this work wrote for the stage, there always was an ethical meaning back of the words and music. Thus we draw our conclusion of the meaning of "Die Meistersinger" story from the wonderful combination of leading motives in the peroration of its Vorspiel.

In his fine book, The Orchestra and Orchestral Music, W. J. Henderson relates this anecdote:

A professional musician was engaged in a discussion of Wagner in the corridor of the Metropolitan Opera House, while inside the orchestra was playing the ‘Meistersinger’ overture.

It is a pity, Said this wise man, in a condescending manner, ‘but Wagner knows absolutely nothing about counterpoint.’

At that instant the orchestra was singing five different melodies at once; and, as Anton Seidl was the conductor, they were all audible.

In a rare book by J. C. Wagenseil, printed in Nuremburg in 1697, are given four "Prize Master Tones." Two of these Wagner has reproduced in modern garb, the former in the Mastersingers’ March, the latter in the Motive of the Art Brotherhood.

Act I. The scene of this act is laid in the Church of St. Catherine, Nuremburg. The congregation is singing the final chorale of the service. Among the worshippers are Eva and her maid, Magdalena. Walther stands aside, and, by means of nods and gestures, communicates with Eva. This mimic conversation is expressively accompanied by interludes between the verses of the chorale, interludes expressively based on the Lyric, Spring, and Prize Song motives, and contrasting charmingly with the strains of the chorale.

The service over, the Motive of Spring, with an impetuous upward rush, seems to express the lovers’ joy that the restraint is removed, and the Lyric Motive resounds exultingly as the congregation departs, leaving Eva, Magdalena, and Walther behind.

Eva, in order to gain a few words with Walther, sends Magdalena back to the pew to look for a kerchief and hymn-book, she has purposely left there. Magdalena urges Eva to return home, but just then David appears in the background and begins putting things to rights for the meeting of the Mastersingers. Magdalena is therefore only too glad to linger. The Mastersinger and Guild motives, which naturally accompany David’s activity, contrast soberly with the ardent phrases of the lovers. Magdalena explains to Walther that Eva is already affianced, though she herself does not know to whom. Her father wishes her to marry the singer to whom at the coming contest the Mastersingers shall award the prize; and, while she shall be at liberty to decline him, she may marry none but a master. Eva exclaims: "I will choose no one but my knight!" Very pretty and gay is the theme heard when David joins the group -- the Apprentice Motive.

How capitally this motive expresses the light-heartedness of gay young people, in this case the youthful apprentices, among whom David was as gay and buoyant as any. Every melodious phrase -- every motive -- employed by Wagner appears to express exactly the character, circumstance, thing, or feeling, to which he applies it. The opening episodes of "Die Meistersinger" have a charm all their own.

The scene closes with a beautiful little terzet, after Magdalena has ordered David, under penalty of her displeasure, to instruct the knight in the art rules of the Mastersingers.

When the ‘prentices enter, they proceed to erect the marker’s platform, but stop at times to annoy the somewhat self-sufficient David, while he is endeavouring to instruct Walther in the rules of the Mastersingers. The merry Apprentice Motive runs through the scene and brings it to a close as the ‘prentices sing and dance around the marker’s box, suddenly, however, breaking off, for the Mastersingers appear.

There is a roll-call and then the fine passage for bass voice, in which Pogner offers Eva’s hand in marriage to the winner of the coming song contest -- with the proviso that Eva adds her consent. The passage is known on concert programmes as "Pogner’s Address."

Walther is introduced by Pogner. The Knight Motive:

Beckmesser, jealous, and determined that Walther shall fail, enters the marker’s box.

Kothner now begins reading off the rules of singing established by the masters, which is a capital take-off on old-fashioned forms of composition and never fails to raise a hearty laugh if delivered with considerable pomposity and unction. Unwillingly enough Walther takes his seat in the candidate’s chair. Beckmesser shouts from the marker’s box: "Now begin!" After a brilliant chord, followed by a superb ascending run on the violins, Walther, in ringing tones, enforced by a broad and noble chord, repeats Beckmesser’s words. But such a change has come over the music that it seems as if that upward rushing run had swept away all restraint of ancient rule and rote, just as the spring wind whirling through the forest tears up the spread of dry, dead leaves, thus giving air and sun to the yearning mosses and flowers. In Walther’s song the Spring Motive forms an ever-surging, swelling accompaniment, finally joining in the vocal melody and bearing it higher and higher to an impassioned climax. In his song, however, Walther, is interrupted by the scatching made by Beckmesser as he chalks the singer’s violation of the rules on the slate, and Walther, who is singing of love and spring, changes his theme to winter, which, lingering behind a thorny hedge is plotting how it can mar the joy of the vernal season. The knight then rises from the chair and sings a second stanza with defiant enthusiasm. As he concludes it Beckmesser tears open the curtains which concealed him in the marker’s box, and exhibits his board completely covered with chalk marks. Walther protests, but the masters, with the exception of Sachs and Pogner, refuse to listen further, and deride his singing. We have here the Motive of Derision.

Sachs protests that, while he found the knight’s art method new, he did not find it formless. The Sachs Motive is here introduced.

The Sachs Motive betoken the genial nature of this sturdy, yet gentle man -- the master spirit of the drama. He combines the force of a conservative character with the tolerance of a progressive one, and is thus the incarnation of the idea which Wagner is working out in this drama, in which the union of a proper degree of conservative caution with progressive energy produces a new ideal in art. To Sach’s innuendo that Beckmessers’ marking hardly could be considered just, as he is a candidate for Eva’s hand, Beckmesser, by way of reply, chides Sachs for having delayed so long in finishing a pair of shoes for him, and as Sachs makes a humorously apologetic answer, the Cobbler Motive is heard.

The sturdy burgher calls to Walther to finish his song in spite of the masters. And now a finale of masterful construction begins. In short, excited phrases the masters chaff and deride Walther. His song, however, soars above all the hubbub. The a’prentices see their opportunity in the confusion, and joining hands they dance around the marker’s box, singing as they do so. We now have combined with astounding skill Walther’s song, the a’prentices’ chorus, and the exclamations of the masters. The latter finally shout their verdict: "Rejected and outsung!" The knight, with a proud gesture of contempt, leaves the church. The a’prentices put the seats and benches back in their proper places, and in doing so greatly obstruct the masters as they crowd toward the doors. Sachs, who has lingered behind, gazes thoughfully at the singer’s empty chair, then, with a humorous gesture of discouragement, turns away.

Act II. The scene of this act represents a street in Nuremberg crossing the stage and intersected in the middle by a narrow, winding alley. There are thus two corner houses -- on the right corner of the alley Pogner’s, on the left Sach’s. Before the former is a linden-tree, before the latter an elder. It is a lovely summer evening.

The opening scene is a merry one. David and the a’prentices are closing shop. After a brisk introduction based on the Midsummer Festival Motive the ‘prentices quiz David on his love affair with Magdalena. The latter appears with a basket of dainties for her lover, but on learning that the knight has been rejected, she snatches the basket away from David and hurries back to the house. The ‘prentices now mockingly congratulate David on his successful wooing. David loses his temper and shows fight, but Sachs, coming upon the scene, sends the ‘prentices on their way and then enters his workshop with David. The music of this episode, especially the ‘prentices’ chorus, is bright and graceful.

Pogner and Eva, returning from an evening stroll, now come down the alley. Before retiring into the house the father questions the daughter as to her feelings concerning the duty she is to perform at the Mastersinging on the morrow. Her replies are discreetly evasive. The music beautifully reflects the affectionate relations between Pogner and Eva. When Pogner, his daughter seated beside him under the linden-tree, speaks of the morrow’s festival and Eva’s part in it in awarding the prize to the master of her choice before the assembled burghers of Nuremburg, the stately Nuremburg Motive is ushered in.

Magdalena appears at the door and signals to Eva. The latter persuades her father that it is too cool to remain outdoors and, as they enter the house, Eva learns from Magdalena of Walther’s failure before the masters. Magdalena advises her to seek counsel with Sachs after supper.

The Cobbler Motive shows us Sachs and David in the former's workshop. When the master has dismissed his ‘prentice till morning, he yields to his poetic love of the balmy midsummer night and, laying down his work, leans over the half-door of his shop as if lost in reverie. The Cobbler Motive dies away to pianissimo, and then there is wafted from over the orchestra like the sweet scent of the blooming elder the Spring Motive, while tender notes on the horn blossom beneath a nebulous veil of tremolo violins into memories of Walther’s song. Its measures run through Sach’s head until, angered at the stupid conservatism of his associates, he resumes his work to the brusque measures of the Cobbler’s Motive. As his ill humour yields again to the beauties of the night, this motive yields once more to that of spring, which with reminiscences of Walther’s first song before the masters, imbues this masterful monologue with poetic beauty of the highest order. The last words in praise of Walther ("The bird who sang to-day," etc.), are sung to a broad and expressive melody.

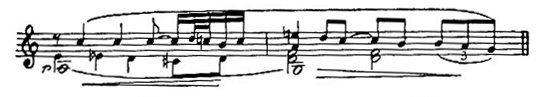

Eva now comes out into the street and, shyly approaching the shop, stands at the door unnoticed by Sachs until she speaks to him. The theme which pervades this scene seems to breathe forth the very spirit of lovely maidenhood which springs from the union of romantic aspirations, feminine reserve, and rare physical graces. It is the Eva Motive, which, with the delicate touch of a master, Wagner so varies that it follows the many subtle dramatic suggestions of the scene. The Eva Motive, in its original form, is as follows:

When at Eva’s first words Sachs looks up, there is this elegant variation of the Eva Motive:

Then the scene being now fully ushered in, we have the Eva Motive itself. Eva leads the talk up to the morrow’s festival, and when Sachs mentions Beckmesser as her chief wooer, roguishly hints, with evident reference to Sachs himself, that she might prefer a hearty widower to a bachelor of such disagreeable characteristics as the marker. There are sufficient indications that the sturdy master is not indifferent to Eva’s charms, but, whole-souled, genuine friend that he is, his one idea is to further the love affair between his fair neighbour and Walther. The music of this passage is very suggestive. The melodic leading of the upper voice in the accompaniment, when Eva asks: "Could not a widower hope to win me?" is identical with a variation of the Isolde Motive in "Tristan and Isolde," while the Eva Motive, shyly pianissimo, seems to indicate the artfulness of Eva’s question. The reminiscence from "Tristan" can hardly be regarded as accidental, for Sachs afterwards boast that he does not care to share the fate of poor King Marke. Eva now endeavours to glean particulars of Walther’s experience in the morning, and we have the Motive of Envy, the Knight Motive, and the Motive of Ridicule. Eva does not appreciate the fine satire in Sach’s severe strictures on Walther’s singing -- he re-echoes not his own views, but those of the others masters, for whom, not for the knights, his strictures are really intended -- and she leaves him in anger. This shows Sachs which way the wind blows, and he forthwith resolves to do all in his power to bring Eva’s and Walther’s love affair to a successful conclusion. While Eva is engaged with Magdalena, who has come out to call her, he busies himself in closing the upper half of his shop door so far that only a gleam of light is visible, he himself being completely hidden. Eva learns from Magdalena of Beckmesser’s intended serenade, and it is agreed that the maid shall personate Eva at the window.

Steps are heard coming down the alley. Eva recognizes Walther and flies to his arms, Magdalena discreetly hurrying into the house. The ensuing ardent scene between Eva and Walther brings familiar motives. The knight’s excitement is comically broken in upon by the Night Watchman’s cow-horn, and, as Eva her hand soothingly upon his arm and counsels that they retreat within the shadow of the linden-three, there steals over the orchestra, like the fragrance of the summer night, a delicate variant of the Eva Motive -- the Summer Night Motive.

Eva vanishes into the house to prepare to elope with Walther. The Night Watchman now goes up the stage intoning a mediaeval chant. Coming in the midst of the beautiful modern music of "The Mastersingers," its effect is most quaint.

As Eva reappears and she and the knight are about to make their escape, Sachs, to prevent this precipitate and foolish step, throws open his shutters and allows his lamp to shed a streak of brilliant light across the street.

The lovers hesitate; and now Beckmesser sneaks in after the Night Watchman and, leaning against Sach’s house, begins to tune his lute, the peculiar twang of which, contrasted with the rich orchestration, sounds irresistibly ridiculous.

Meanwhile, Eva and Walther have once more retreated into the shade of the linden-tree, and Sachs, who has placed his work bench in front of his door, begins hammering at the last and intones a song which is one of the rough diamonds of musical invention, for it is purposely brusque and rough, just such a song as a hearty, happy artisan might sing over his work. It is aptly introduced by the Cobbler Motive. Beckmesser, greatly disturbed lest his serenade be ruined, entreats Sachs to cease singing. The latter agrees, but with the proviso that he shall "mark" each of Beckmesser’s mistakes with a hammer stroke. As if to bring out as sharply as possible the ridiculous character of the serenade, the orchestra breathes forth once more the summer night’s music before Beckmesser begins his song, and this is set to a parody of the Lyric Motive. Wagner, with keen satire, seems to want to show how a beautiful melody may become absurd through old-fogy methods. Beckmesser has hardly begun before Sach’s hammer comes down on the last with a resounding whack, which makes the town clerk fairly jump with anger. He resume, but soon is rudely interrupted again by a blow of Sach’s hammer. The whacks come faster and faster. Beckmesser, in order to make himself heard above them, sings louder and louder. Some of the neighbours are awakened by the noise and coming to their windows bid Beckmesser hold his peace. David, stung by jealousy as he sees Magdalena listening to the serenade, leaps from his room and falls upon the town clerk with a cudgel. The neighbours, male and female, run out into the street and a general melée ensues, the masters, who hurry upon the scene, seeking to restore quiet, while the ‘prentices vent their high spirits by doing all in their power to add to the hubbub. All is now noise and disorder, pandemonium seeming to have been let loose upon the dignified old town.

Musically this tumult finds expression in a fugue whose chief theme is the Cudgel Motive.

From beneath the hubbub of voices -- those of the ‘prentices and journeymen, delighted to take part in the shindy, of the women who are terrified at it, and of the masters who strive to stop it, is heard the theme of Beckmesser’s song, the real cause of the row This is another of those many instances in which Wagner vividly expresses in his music the significance of what transpires on the stage.

Sachs finally succeeds in shoving the ‘prentices and journeymen out of the way. The street is cleared, but not before the cobbler-poet has pushed Eva, who was about to elope with Walther, into her father’s arms and drawn Walther after him into his shop.

The street is quiet. And now, the rumpus subsided and all concerned in it gone, the Night Watchman appears, rubs his eyes and chants his mediaeval call. The street is flooded with moonlight. The Watchman with his clumsy halberd lunges at his own shadow, then goes up the alley.

We have had hubbub, we have had humour, and now we have a musical ending elvish, roguish, and yet exquisite in sentiment. The effect is produced by the Cudgel Motive played with the utmost delicacy on the flute, while the theme of Beckmesser’s serenade merrily runs after itself on clarinet and bassoon, and the muted violins softly breathe the Midsummer Festival Motive.

Act III. During this act the tender strain in Sach’s sturdy character is brought out in bold relief. Hence the prelude develops what may be called three Sachs themes, two of them expressive of his twofold nature as poet and cobbler, the third standing for the love which his fellow-burghers bear him.

The prelude opens with the Wahn Motive or Motive of Poetic Illusion. This reflects the deep thought and poetic aspirations of Sachs the poet. It is followed by the theme of the beautiful chorus, sung later in the act, in praise of Sachs: "Awake! Draws nigh the break of day." This theme, among the three heard in the prelude, points to Sach’s popularity. The third consists of portions of the cobbler’s song in the second act. This prelude has long been considered one of Wagner’s masterpieces. The themes are treated with the utmost delicacy, so that we recognize through them both the tender, poetic side of Sach’s nature and his good-humoured brusqueness. The Motive of Poetic Illusion is deeply reflective, and it might be preferable to name it the Motive of Poetic Thought, were it not that it is better to preserve the significance of the term Wahn Motive, which there is ample reason to believe originated with Wagner himself. The prelude is, in fact, a subtle analysis of character expressed in music.

How peaceful the scene on which the curtain rises. Sachs is sitting in an arm-chair in his sunny workshop, reading in a large folio. The Illusion Motive has not yet died away in the prelude, so that it seems to reflect the thoughts awakened in Sachs by what he is reading. David, dressed for the festival, enters just as the prelude ends. There is a scene full of charming bonhomie between Sachs and his ‘prentice, which is followed, when the latter has withdrawn, by Sach’s monologue: "Wahn! Wahn! Ueberall Wahn!" (Illusion, everywhere illusion.)

While the Illusion Motive seems to weave a poetic atmosphere about him, Sachs buried in thought, rests his head upon his arm over the folio. The Illusion Motive is followed by the Spring Motive, which in turn yields to the Nuremburg Motive as Sachs sings the praises of the stately old town. At his reference to the tumult of the night before there are in the score corresponding allusions to the music of that episode. "A glowworm could not find its mate," he sings, referring to Walther and Eva. The Midsummer Festival, Lyric, and Nuremburg motives in union foreshadow the triumph of true art through love on Nuremburg soil, and thus bring the monologue to a stately conclusion.

Walther now enters from the chamber, which opens upon a gallery, and, descending into the workshop, is heartily greeted by Sachs with the Sachs Motive, which dominates the immediately ensuing scene. Very beautiful is the theme in which Sachs protest against Walther’s derision of the masters; for they are, in spite of their many old-fogyish notions, the conservators of much that is true and beautiful in art.

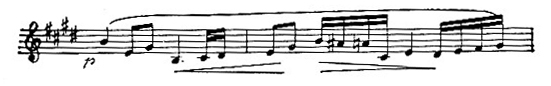

Walther tells Sachs of a song which came to him in a dream during the night, and sings two stanzas of this "Prize Song," Sachs making friendly critical comments as he writes down the words. The Nuremburg Motive in sonorous and festive instrumentation closes this melodious episode.

When Sachs and Walther have retired Beckmesser is seen peeping into the shop. Observing that it is empty he enter hastily. He is ridiculously overdressed for the approaching festival, limps, and occasionally rubs his muscles as if he were still stiff and sore from his drubbing. By chance his glance falls on the manuscript of the "Prize Song" in Sach’s handwriting on the table, when he breaks forth in wrathful exclamations, thinking now that he has in the popular master a rival for Eva’s hand. Hearing the chamber door opening he hastily grabs the manuscript and thrusts it into his pocket. Sachs enters. Observing that the manuscript is no longer on the table, he realizes that Beckmesser has stolen it, and conceives the idea of allowing him to keep it, knowing that the marker will fail most wretchedly in attempting to give musical expression to Walther’s inspiration.

The scene places Sachs in a new light. A fascinating trait of his character is the dash of scapegrace with which it is seasoned. Hence, when he thinks of allowing Beckmesser to use the poem the Sachs Motive takes on a somewhat facetious, roguish grace. There now ensues a charming dialogue between Sachs and Eva, who enters when Beckmesser has departed. This is accompanied by a transformation of the Eva Motive, which now reflects her shyness and hesitancy in taking Sachs into her confidence.

With it is joined the Cobbler Motive when Eva places her foot upon the stool while Sachs tries on the shoes she is to wear at the festival. When, with a cry of joy, she recognizes her lover as he appears upon the gallery, and remains motionless, gazing upon him as if spellbound, the lovely Summer Night Motive enhances the beauty of the tableau. While Sachs cobbles and chats away, pretending not to observe the lovers, the Motive of Maidenly Reserve passes through many modulations until there is heard a phrase from "Tristan and Isolde" (the Isolde Motive), an allusion which is explained below. The Lyric Motive introduces the third stanza of Walther’s "Prize Song," with which he now greets Eva, while she, overcome with joy at seeing her lover, sinks upon Sach’s breast. The Illusion Motive rhapsodizes the praises of the generous cobbler-poet, who seeks relief from his emotions in bantering remarks, until Eva glorifies him in a noble burst of love and gratitude in a melody derived from the Isolde Motive.

It is after this that Sachs, alluding to his own love of Eva, exclaims that he will have none of King Marker’s triste experience; and the use of the King Marke Motive at this point shows that the previous echoes of the Isolde Motive were premeditated rather than accidental.

Magdalena and David now enter, and Sachs gives to Walther’s "Prize Song" its musical baptism, utilizing chiefly the first and second lines of the chorale which opens the first act. David then kneels down and, according to the custom of the day, receives from Sachs a box on the ear in token that he is advanced from ‘prentice to journeyman. Then follows the beautiful quintet, in which the "Prize Song," as a thematic germ, puts forth its loveliest blossoms. This is but one of many instances in which Wagner proved that when the dramatic situation called for it he could conceive and develop a melody of most exquisite fibre.

After the quintet the orchestra resumes the Nuremburg Motive and all depart for the festival. The stage is now shut off by a curtain behind which the scene is changed from Sach’s workshop to the meadow on the banks of the Pegnitz, near Nuremburg. After a tumultuous orchestral interlude which portrays by means of motives already familiar, with the addition of the fanfare of the town musicians, the noise and bustle incidental to preparations for a great festival, the curtain rises upon a lively scene. Boats decked out in flags and bunting and full of festively clad members of the various guilds and their wives and children are constantly arriving. To the right is a platform decorated with the flags of the guilds which have already gathered. People are making merry under tents and awnings where refreshments are served. The ‘prentices are having a jolly time of it heralding and marshalling the guilds who disperse and mingle with the merrymakers after the standard bearers have planted their banners near the platform.

Soon after the curtain rises the cobblers arrive, and as they march down the meadow, conducted by the ‘prentices, they sing in honour of St. Cripin, their patron saint, a chorus, based on the Cobbler Motive, to which a melody in popular style is added. The town watchmen, with trumpets and drums, the town pipers, lute makers, etc. and then the journeymen, with comical sounding toy instruments, march past, and are succeeded by the tailors, who sing a humorous chorus, telling how Nuremburg was saved from its ancient enemies by a tailor, who sewed a goatskin around him and pranced around on the town walls, to the terror of the hostile army, which took him for the devil. The bleating of a goat is capitally imitated in this chorus.

With the last chord of the tailors’ chorus the bakers strike up their song and are greeted in turn by cobblers and tailors with their respective refrains. A boatful of young peasant girls in gay costumes now arrives, and the ‘prentices make a rush for the bank. A charming dance in waltz time is struck up. The ‘prentices with the girls dance down toward the journeymen, but as soon as these try to get hold of the girls, the ‘prentices veer off with them in another direction. This veering should be timed to fall at the beginning of those periods of the dance to which Wagner has given, instead of eight, measures, seven and nine, in order by this irregularity to emphasize the ruse of the ‘prentices.

The dance is interrupted by the arrival of the masters, the ‘prentices falling in to receive, the others making room for the procession. The Mastersingers advance to the stately strains of the Mastersinger Motive, which, when Kothner appears bearing their standard with the figure of King David playing on his harp, goes over into the sturdy measures of the Mastersingers’ March. Sachs rises and advances. At sight of him the populace intone the noblest of all choruses: "Awake! Draws nigh the break of day," the words of which are a poem by the real Hans Sachs.

At its conclusion the populace break into shouts in praise of Sachs, who modestly yet most feelingly gives them thanks. When Beckmesser is led to the little mound of turf upon which the singer is obliged to stand, we have the humorous variation of the Mastersinger Motive from the Prelude. Beckmesser’s attempt to sing Walther’s poem ends, as Sachs had anticipated, in utter failure. The town clerk’s effort is received with jeers. Before he rushes away, infuriated but utterly discomfited, he proclaims that Sachs is the author of the song they have derided. The cobbler-poet declares to the people that it is not by him; that it is a beautiful poem if sung to the proper melody and that he will show them the author of the poem, who will in song disclose its beauties. He then introduces Walther. The knight easily succeeds in winning over people and masters, who repeat the closing melody of his "Prize Song" in token of their joyous appreciation of his new and wondrous art. Pogner advances to decorate Walther with the insignia of the Mastersingers’ Guild.

In more ways than one the "Prize Song" is a mainstay of "Die Meistersinger." It has been heard in the previous scene of the third act, not only when Walther rehearses it for Sachs, but also in the quintet. Moreover, versions of it occur in the overture and indeed, throughout the work, adding greatly to the romantic sentiment of the score. For "Die Meistersinger" is a comedy of romance.

In measures easily recognized from the Prelude, to which the Nuremburg Motive is added, Sachs now praises the masters and explains their noble purpose as conservators of art. Eva takes the wreath with which Walther has been crowned, and with it crowns Sachs, who has meanwhile decorated the knight with the insignia. Pogner kneels, as if in homage, before Sachs, the masters point to the cobbler as to their chief, and Walther and Eva remain on either side of him, leaning gratefully upon his shoulders. The chorus repeats Sach’s final admonition to the closing measures of the Prelude.

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-23 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |