Music with Ease > Operas of Richard Wagner > Tannhäuser (Wagner) - Synopsis

Tannhäuser - Synopsis

An Opera by Richard Wagner

Original German title: Tannhäuser und der Sängerkrieg auf der Wartburg

Opera in three acts, words and music by Richard Wagner. Produced, Royal Opera, Dresden, October 19, 1845. Paris, Grand Opéra. March 13, 1861. London, Covent Garden, May 6, 1876, in Italian; Her Majesty’s Theatre, February 14, 1882, in English; Drury Lane, May 23, 1882, in German, under Hans Richter. New York, Stadt Theatre, April 4, 1859, and July, 1861, conducted by Carl Bergmann; under Adolff Neuendorff’s direction, 1870, and, Academy of Music, 1877; Metropolitan Opera House, opening night of German Opera, under Dr. Leopold Damrosch, November 17, 1884, with Seidl-Kraus as Elizabeth, Anna Slach as Venus, Schott as Tannhäuser, Adolf Robin son as Wolfram, Josef Kogel as the Landgrave.

CHARACTERS

HERMANN, Landgrave of Thuringia………………….….…. Bass

TANNHAUSER, a Knight/Minnesinger …… …………………Tenor

WOLFRAM VON ESCHENBACH, a Knight/Minnesinger… Baritone

WALTER VON DER VOGELWEIDE, a Knight/Minnesinger…Tenor

BITEROLF, a Knight/Minnesinger… ………… ……………… Bass

HEINRICH DER SCHREIBER, a Knight/Minnesinger……… Tenor

REINMAR VON ZWETER , a Knight/Minnesinger…… ………Bass

ELIZABETH, niece of the Landgrave………………… Soprano

VENUS…………………………………………………… Soprano

A YOUNG SHEPHERD…………………………………. Soprano

FOUR NOBLE PAGES………………………………….. Soprano and Alto

Nobles, Knights, Ladies, elder and younger Pilgrims, Sirens, Niads, Nymphs, Bacchantes.

Time: Early Thirteenth Century.

Place: Near Eisenach.

The story of "Tannhäuser" is laid in and near the Wartburg, where, during the thirteenth century, the Landgraves of the Thuringian Valley held sway. They were lovers of arts, especially of poetry and music, and at the Wartburg many peaceful contests between the famous minnesingers (or minstrels) took place. Near this castle rises the Venusberg. According to tradition the interior of this mountain was inhabited by Holda, the Goddess of Spring, who, however, in time became identified with the Goddess of Love. Her court was filled with nymphs and sirens, and it was her greatest joy to entice into the mountain the knights of the Wartburg and hold them captive to her beauty.

Among those whom she has thus lured into the rosy recesses of the Venusberg is Tannhäuser.

In spite of her beauty, however, he is weary of her charms and longs for a glimpse of the world. He seems to have heard the tolling of bells and other earthly sounds, and these stimulate his yearning to be set free from the magic charms of the goddess.

In vain she prophesies evil to him should be return to the world. With the cry that his hope rests in the Virgin, he tears himself away from her. In one of the swiftest and most effective of scenic changes the court of Venus disappears and in a moment we see Tannhäuser prostrate before a cross in a valley upon which the Wartburg peacefully looks down. Pilgrims on their way to Rome pass him by and Tannhäuser thinks of joining them in order that at Rome he may obtain forgiveness for his crime in allowing himself to be enticed into the Venusberg. But at that moment the Landgraves and a number of minnesingers on their return from the chase come upon him and, recognizing him, endeavour to persuade him to return to the Wartburg with them. Their pleas, however, are vain, until one of them, Wolfram von Eschenbach, tells him that since he has left the Wartburg a great sadness has come over the niece of the Landgrave, Elizabeth. It is evident that Tannhäuser has been in love with her, and that it is because of her beauty an virtue that he regrets so deeply having been lured into the Venusberg. For Wolfram’s words stir him profoundly. To the great joy of all , he agrees to return to the Wartburg, the scene of his many triumphs as a minnesinger in the contests of song.

The Landgrave, feeling sure that tannhauser will win the prize at the contest of song soon to be held, offers the hand of his niece to the winner. The minnesingers sing tamely of the beauty of virtuous love, but Tannhäuser, suddenly remembering the seductive and magical beauties of the Venusberg, cannot control himself, and bursts out into a reckless hymn in praise of Venus. Horrified at his words, the knights draw their swords and would slay him, but Elizabeth throws herself between him and them. Crushed and penitent, Tannhäuser stands behind her, and the Landgrave, moved by her willingness to sacrifice herself for her sinful lover, announces that he will be allowed to join a second band of pilgrims who are going to Rome and to plead with the Pope for forgiveness.

Elizabeth prayerfully awaits his return; but, as she is kneeling by the crucifix in front of the Wartburg, the Pilgrims pass her by and in the band she does not see her lover. Slowly and sadly she returns to the castle to die. When the Pilgrims voices have died away, and Elizabeth has returned to the castle, leaving only Wolfram, who is also deeply enamoured of her, upon the scene, Tannhäuser appears, weary and dejected. He has sought to obtain forgiveness in vain. The Pope has cast him out forever, proclaiming that no more than that his staff can put forth leaves can he expect forgiveness. He has come back to re-enter the Venusberg. Wolfram seeks to restrain him, but it is not until he invokes the name of Elizabeth that Tannhäuser is saved. A cortege approaches, and, as tannhauser recognizes the form of Elizabeth on the bier, he sinks down on her coffin and dies. Just then the second band of pilgrims arrive, bearing Tannhäuser’s staff, which has put forth blossoms, thus showing that his sins have been forgiven.

From "The Flying Dutchman" to "Tannhäuser," dramatically and musically, is, if anything, a greater stride than from "Rienzi" to "The Flying Dutchman." In each of his successive works Wagner demonstrates greater and deeper powers as a dramatic poet and composer. True it is that in nearly every one of them woman appears as the redeeming angel of sinful man, but the circumstances differ so that this beautiful tribute always interests us anew.

The overture of the opera has long been a favorite piece on concert programs. Like that of "The Flying Dutchman" it is the story of the whole opera told in music. It certainly is one of the most brilliant and effective pieces of orchestral music and its popularity is easily understood. It opens with the melody of the Pilgrim’s chorus, beginning softly as if coming from a distance and gradually increasing in power until it is heard in all its grandeur. At this point it is joined by a violently agitated accompaniment on the violins. This passage evoked great criticism when it was first produced and for many years thereafter. It was thought to mar the beauty of the pilgrims’ chorus. But without doing so at all it conveys additional dramatic meaning, for these agitated phrases depict the restlessness of the world as compared with the grateful tranquility of religious faith as set forth in the melody of the Pilgrims’ chorus.

Having reached a climax, this chorus gradually dies away, and suddenly, and with intense dramatic contrast, we have all the seductive spells of the Venusberg displayed before us-that is, musically displayed; but then the music is so wonderfully vivid, it depicts with such marvelous clearness the many-coloured alluring scene at the court of the unholy goddess, it gives vent so freely to the sinful excitement which pervades the Venusberg, that we actually seem to see what we hear. This passes over in turn to the impassioned burst of song in which tannhauser hymns Venus’s praise, and immediately after we have the boisterous and vigorous music which accompanies the threatening action of the Landgrave and minnesingers when they draw their swords upon Tannhäuser in order to take vengeance upon him for his crimes. Upon these three episodes of the drama, which so characteristically give insight into its plot and action, the overture is based, and it very naturally concludes with the Pilgrims’ chorus which seems to voice the final forgiveness of Tannhäuser.

The curtain rises, disclosing all the seductive spells of the Venusberg. Tannhäuser lies in the arms of Venus, who reclines upon a flowery couch. Nymphs, sirens, and satyrs are dancing about them and in the distance are grottoes alive with amorous figures. Various mythological amours, such as that of Leda and the swan, are supposed to be in progress, but fortunately at a mitigating distance.

Much of the music familiar from the overture is heard during this scene, but it gains in effect from the distant voices of the sirens and, of course, from artistic scenery and grouping and well-executed dances of the denizens of Venus court. Very dramatic, too, is the scene between Venus and Tannhäuser, when the latter sings his hymn in her praise, but at the same time proclaims that he desires to return to the world. In alluring strains she endeavours to tempt him to remain with her, but when she discovers that he is bound upon going, she vehemently warns him of the misfortunes which await him upon earth and prophesies that he will some day return to her and penitently ask to be taken back into her realm.

Dramatic and effective as this scene is in the original score, it has gained immensely in power by the additions which Wagner made for the production of the work in Paris, in 1861. The overture does not, in this version, come to a format close, but after the manner of Wagner’s later works, the transition is made directly from it to the scene of the Venusberg. The dances have been elaborated and laid out upon a more careful allegorical basis and the music of Venus has been greatly strengthened from a dramatic point of view, so that now the scene in which she pleads with him to remain and afterwards warns him against the sorrows to which he will be exposed, are among the finest of Wagner’s composition, rivalling in dramatic power the ripest work in his music-dramas.

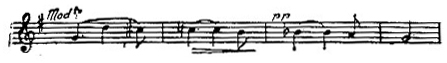

Wagner’s knowledge of the stage is shown in the wonderfully dramatic effect in the change of scene from the Venusberg to the landscape in the valley of the Wartburg. One moment we have the variegated allures of the court of the Goddess of Love, with its dancing nymphs, sirens, and satyrs, its beautiful grottoes and groups; the next all this has disappeared and from the heated atmosphere of Venus’s unholy rites we are suddenly transported to a peaceful scene whose influence upon us is deepened by the crucifix in the foreground, before which Tannhäuser kneels in penitence. The peacefulness of the scene is further enhanced by the appearance upon a rocky eminence to the left of a young Shepherd who pipes a pastoral strain, while in the background are heard the tinkling of bells, as though his sheep were there grazing upon more upland meadow. Before he has finished piping his lay the voices of the Pilgrims are heard in the distance, their solemn measures being interrupted by little phrases piped by the Shepherd. As the Pilgrims approach, the chorus becomes louder, and as they pass over the stage and bow before the crucifix, their praise swells into an eloquent psalm of devotion.

Tannhäuser is deeply affected and gives way to his feelings in a lament, against which are heard the voices of the Pilgirms as they recede in the distance. This whole scene is one of marvelous beauty, the contrast between it and the preceding episode being enhanced by the religiously tranquil nature of what transpires and of the accompanying music. Upon this peaceful scene the notes of hunting-horns now break in, and gradually the Landgrave and his hunters gather about Tannhäuser. Wolfram recognizes him and tells the others who he is. They greet him in an expressive septette, and Wolfram, finding he is bent upon following the Pilgrims to Rome, asks permission of the Landgrave to inform him of the impression which he seems to have made upon Elizabeth. This he does in a melodious solo, and Tannhäuser, overcome by his love for Elizabeth, consents to return to the halls which have missed him so long. Exclamations of joy greet his decision, and the act closes with a enthusiastic ensemble, which is a glorious piece of concerted music, and never fails of brilliant effect when it is well executed, especially if the representative of Tannhäuser has a voice that can soar above the others, which, unfortunately, is not always the case. The accompanying scenic grouping should also be in keeping with the composer’s instructions. The Landgrave’s suite should gradually arrive, bearing the game which has been slain, and horses and hunting-hounds should be led on the stage. Finally, the Landgrave and minnesingers mount their steeds and ride away toward the castle.

The scene of the second is laid in the singer’s hall of the Wartburg. The introduction depicts Elizabeth’s joy at Tannhäuser’s return, and when the curtain rises she at once enters and joyfully greets the scenes of Tannhäuser’s former triumphs in broadly dramatic melodious phrases. Wolfram then appears, conducting Tannhäuser to her. Elizabeth seems overjoyed to see him, but then checks herself, and her maidenly modesty, which veils her transport at meeting him, again finds expression in a number of hesitating but exceedingly beautiful phrases. She asks Tannhäuser where he has been, but he, of course, gives misleading answers. Finally, however, he tells her she is the one who has attracted him back to the castle. Their love finds expression in a swift and rapidly flowing dramatic duet, which unfortunately is rarely given in its entirely, although as a glorious outburst of emotional music it certainly deserves to be heard in the exact form and length in which the composer wrote it.

There is then a scene of much tender feeling between the Landgrave and Elizabeth, in which the former tells her that he will offer her hand as prize to the singer whom she shall crown as winner. The first strains of the grand march are the heard. This is one of Wagner’s most brilliant and effective orchestral and vocal pieces. Though in perfect march rhythm, it is not intended that the guests who assembled at the Wartburg shall enter like a company of soldiers. On the contrary, they arrive in irregular detachments, stride across the floor, and make their obeisance in a perfectly natural manner. After an address by the Landgrave, which can hardly be called remarkably interesting, the singers draw lots to decide who among them shall begin. This prize singing is, unfortunately, not so great in musical value as the rest of the score, and, unless a person understands the words, it is decidedly long drawn out. What, however, redeems it is a gradually growing dramatic excitement as Tannhäuser voices his contempt for what seem to him the tame tributes paid to love by the minnesingers, an excitement which reaches its climax when, no longer able to restrain himself, he burst forth into his hymn in praise of the unholy charms of Venus.

The women cry out in horror and rush from the hall as if the very atmosphere were tainted by his presence, and the men, drawing their swords, rush upon him. This brings us to the great dramatic moment, when, with a shriek, Elizabeth, in spite of his betrayal of her love, throws herself protectingly before him, and thus appears a second time as his saving angel. In short and excited phrases the men pour forth their wrath at Tannhäuser‘s crime in having sojourned with Venus, and he, realizing its enormity, seems crushed with a consciousness of his guilt. Of wondrous beauty is the septette, "An angel has from heaven descended," which rises to a magnificent climax and is one of the finest pieces of dramatic writing in Wagner’s scores, although often execrably sung and rarely receiving complete justice. The voices of young Pilgrims are heard in the valley. The Landgrave then announces the conditions upon which Tannhäuser can again obtain forgiveness, and Tannhäuser joins the pilgrims on their way to Rome.

The third act displays once more the valley of the Wartburg, the same scene as that to which the Venusberg changed in the first act. Elizabeth, arrayed in white, is kneeling, in deep prayer, before the crucifix. At one side, and watching her tenderly, stands Wolfram. After a sad recitative from Wolfram, the chorus of returning Pilgrims is heard in the distance. They sing the melody heard in the overture and in the first act; and the same effect of gradual approach is produced by a superb crescendo as they reach and cross the scene. With almost piteous anxiety and grief Elizabeth scans them closely as they go by, to see if Tannhäuser be among them, and when the last one has passed and she realizes that he has not returned, she sinks again upon her knees before the crucifix and sings the prayer, "Almighty Virgin, hear my sorrow," music in which there is most beautifully combined the expression of poignant grief with trust in the will of the Almighty. As she rises and turns toward the castle, Wolfram, by his gesture, seems to ask her if he cannot accompany her, but she declines his offer and slowly goes her way up the mountain.

Meanwhile night has fallen upon the scene and the evening star glows softly above the castle. It is then that Wolfram, accompanying himself on his lyre, intones the wondrously tender and beautiful "Song to the Evening Star," confessing therein his love for the saintly Elizabeth.

then Tannhäuser, dejected, footsore, and weary, appears and in broken accents asks Wolfram to show him the way back to the Venusberg. Wolfram bids him stay his steps and persuades him to tell him the story of his pilgrimage. In fierce, dramatic accents, Tannhäuser relates all that he has suffered on his way to Rome and the terrible judgment pronounced upon him by the Pope. This is a highly impressive episode, clearly foreshadowing Wagner’s dramatic use of musical recitative in his later music-dramas. Only a singer of the highest rank can do justice to it.

Tannhäuser proclaims that, having lost all chance of salvation, he will once more give himself up to the delights of the Venusberg. A roseate light illumines the recesses of the mountain and the unholy company of the Venusberg again is seen, Venus stretching out her arms for Tannhäuser, to welcome him. But at last, when Tannhäuser seems unable to resist Venus’ enticing voice any longer, Wolfram conjures him by the memory of the sainted Elizabeth. Then Venus knows that all is lost. The light dies away and the magic charms of the Venusberg disappear. Amid tolling of bells and mournful voices a funeral procession comes down the mountain. Recognizing the features of Elizabeth, the dying Tannhäuser falls upon her corpse. The younger pilgrims arrive with the staff, which has again put forth leaves, and amid the hallelujahs of the pilgrims the opera closes.

Besides the character of Elizabeth that of Wolfram stands out for its tender, manly beauty. In love with Elizabeth, he is yet the means of bringing back her lover to her, and in the end saves that lover from perdition, so that they may be united in death.

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-23 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |