Music with Ease > Operas of Richard Wagner > The Valkyrie (Wagner)

The Valkyrie

(German title: Die Walküre)

An Opera by Richard Wagner

Dramatis Personae

SIEGMUND, the Walsung

SIEGLINDE, his Sister

HUNDING, Husband of Sieglinde

WOTAN

FRICKA

The Valkyries, Daughters of Wotan:

BRÜNNHILDE

GERHILDE

ORTLINDE

WALTRAUTE

SVERTLEITE

HELMWIGE

SIGRUNE

GRIMGREDE

ROSSWEISE

Plot and Music of The Valyrie

Before the opening of "The Valkyrie" many events have taken place. Wotan has begotten the nine Valkyries (literally choosers of the slain), whose mission it is to bring to Walhalla the souls of the heroes who have fallen in battle. Moreover, to escape the evil influence of Alberich’s curse, Wotan has descended to earth, and, under the name of Volse, has begotten the Volsung twins, Siegmund and Sieglinde. These he leaves to be trained in the school of adversity, hoping that Siegmund will kill Fafner and restore the gold to the Rhine-maidens.

The orchestral introduction is of a turbulent and stormy character, the incessant triplets of the violins being "suggestive of hail and rain beating on the leaves of tall trees, while the rolling figure in the bass seems to indicate the angry voice of thunder." The storm subsides and the curtain rises, disclosing the interior of Hunding’s roughly-built timber dwelling. From the center of the empty room rises the trunk of a great tree, type of the world’s ash, Yggdrasil. A fire is burning. Siegmund enters, and drops down by the hearth, weaponless and half dead with fatigue. Sieglinde emerges from an inner chamber to gaze in astonishment at the stranger. Noting his exhausted condition, she refreshes him with food and drink, both looking the while into each other’s eyes with an interest not yet conscious of the kinship between them. Music of extraordinary beauty and pathos portrays their powerful mutual attraction.

Siegmund asks to know where he is, and is informed in reply that house and wife belong to Hunding, whose arrival is soon after announced by the sound of his horse’s hoof. Sieglinde hastily opens the door. Hunding enters, pausing on the threshold as he notes the presence of the stranger: noting also, presently, the likeness between Siegmund and Sieglinde, especially the "glittering serpent" in the eyes of each. Sieglinde tells of the coming of Siegmund; and Hunding gives the guest a grudging welcome. Sieglinde proceeds to prepare a meal, while Siegmund, at Hunding’s invitation, recounts his adventures.

Beginning with his early life, he narrates how, "coming home from the forest, his father and he found their home destroyed by enemies, the mother killed, the sister carried off; how, after that, they lived the lives of outlaws, at war with the world, till at last his father was taken from him. Separated from his father in battle, Siegmund had followed his trace everywhere, but at last, finding an empty wolf-skin, his father’s dress, concluded him to be slain." His last fight, Siegmund continues, has been to protect a maiden from her brothers, who were determined to wed her to an unloved man. He slew the brothers, but the vassals of the dead men crowded on Siegmund; the maid died; and Siegmund was compelled to fly and seek rest for the night in Hunding’s hut.

Such, inbrief, was Siegmund’ story. "For one night," his host makes answer, "my house shall be thy refuge, but to-morrow, see to thy weapon, for thou shalt pay with thy life for the dead." For Hunding himself, be it observed, is one of the tribe with whom Siegmund has fought that day.

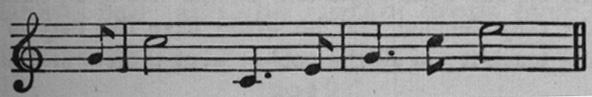

Left alone by the dying firelight, Siegmund broods over his impending doom. He reflects sadly how fate has delivered him, with no means of defence, into the hands of his bitterest enemy. Suddenly there is a stirring of the embers, and from the sparks a sharp light is thrown on a particular part of the ash tree, to which Sieglinde when leaving the room had furtively but vainly directed Siegmund’s attention. There Siegmund now makes out the hilt of a sword -- the very weapon which his father had promised him in his highest need -- while the trumpets give out the Sword theme with almost startling effect --

The fire dies down completely; darkness reigns. The door opens softly, and Sieglinde reappears. Her husband, she says, lies in deepest sleep, for she has come to urge Siegmund to flight, and to point out to him the weapon close at his hand, the sword in the ash tree. The description of her wedding to Hunding, to whom she has been sold against her will, and the account she gives of the mysterious sword are almost a literal counterpart of the old tale in the Volsunga Saga, which it may therefore be interesting to quote:

In a word, many had tried in vain: the sword still remained fast in the tree. Tender emotions follow these warlike thoughts. Siegmund draws Sieglinde to his breast, and in a song of spring and love, sweeter perhaps than ever music and poetry combined to bring forth, declares that they are destined for each other --

It is a marvellous love-scene altogether. Sieglinde has been struck from the first with the stranger’s resemblance to herself, and now she asks for his real name. The disclosure is made: Siegmund is no Wolfing but a Volsung, and Sieglinde hails him by that name. "This sword," she says, as she proclaims herself his sister, "has been destined for thee by our father Volsung." With a mighty wrench, and with the exultant cry, "Nothung! Nothung! name I this sword!" Siegmund tears the weapon from the tree, and Sieglinde throws herself on his breast in a transport of desire. The avowal of their relationship cannot quench the passion of the unfortunate pair, and the curtain drops over the subsequent scene.

This episode, this illicit love of brother and sister, used to be, and still sometimes is, objected to as a shock to modern feelings. It is, however, as a critic pointed out so long ago as 1876, a vital ingredient of Wagner’s story, and has been treated by him in the open and therefore chaste spirit of the old myth itself. It must be remembered that we are not dealing here with ordinary men and women, but with the children of a god -- mythical beings, that is, who have hardly yet emerged from the state of natural forces. Who has ever been shocked at the amours of the Greek divinities on account of their being within the forbidden degrees of relationship, or even at the intermarriages of the children of Adam and Eve, which the Pentateuch implies? The tragic guilt for which Sieglinde suffers does not lie in her love for her brother, but in the breach of her marriage vow. The punishment of this guilt is now rapidly approaching.

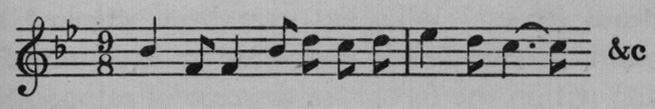

When the curtain rises on the Second Act it is to expose a wild and rocky pass. Wotan is instructing Brünnhilde, his favourite Valkyrie daughter, to assist Siegmund in the impending combat with Hunding. Here the discerning musical listener will note a couple of motives specially associated with Brünnhilde in her character of Valkyrie. One is the Valkyrie’s call, frequently repeated; the other, used afterwards whenever the nature of the Valkyrie has to be emphasised, seems to be designed rhythmically to suggest the motion of the Valkyrie steed --

Suddenly Fricka’s chariot, drawn by two rams, is seen approaching, and Brünnhilde disappears, with her wild Valkyrie cry. Fricka has come to demand vengeance for Siegmund’s unlawful act in carrying off Sieglinde. She complains of the injury done to her, the protectress of marriage, by Siegmund and his sister. She insists that Wotan shall punish his children. Wotan pleads the power of love in their favour; reminding Fricka that Sieglinde had accepted a husband against her own inclinations. Fricka refuses to listen. She charges Wotan with unfaithfulness to her. It was he, she asserts, who, as Volsung, "roamed the woods and became the father of Siegmund and Sieglinde, and bids him finish his work and trample on her in triumph." The sinful Siegmund, she reiterates, must die. Brünnhilde’s voice is heard from the heights, and on her appearance, Fricka extracts from Wotan an oath that Siegmund shall fall.

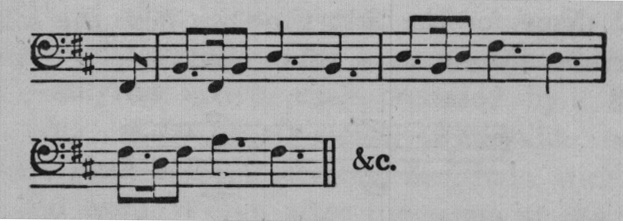

Wotan then confides his hopes to Brünnhilde, but enjoins her to obey Fricka’s mandate; and they, too depart. Siegmund and Sieglinde enter, and the wearied woman falls swooning in her brother’s arms. Now for the first time we hear the solemn, mysterious Fate-motive, often used later-

Brünnhilde reappears, and in an enchanting scene announces to Siegmund his approaching end, telling him at the same time that the joys of Walhalla await him. Siegmund passionately protests that he will not die or go to Walhalla without his bride; and Brünnhilde, moved by his entreaties, by his bravery and the ardour of his love for Sieglinde, promises to aid him in the fight, in accordance with Wotan’s secret wish. This she does when the combatants have met on a lofty rock, but Wotan thrusts his spear between them, so that Siegmund’s sword is shattered upon it. Siegmund is slain by Hunding, who is himself then stricken to death by a contemptuous wave of Wotan’s hand. With the exit of Wotan, vowing vengeance on Brünnhilde, the Act ends.

The prelude to the Third Act is the familiar Ride of the Valkyrie, so often heard in the concert-room --

The curtain rises on another wild scene -- on the Valkyries’ rock, where four of the Valkyries are assembled after their celestial ride. Again there is storm and tempest. One after another the rest of the Valkyries arrive, each preceded by a flash of lighting. Last of all comes Brünnhilde, carrying the terrified, half- unconscious Sieglinde, with whom she fled from Wotan after the scene at the end of the previous Act. Brünnhilde hands Sieglinde the splintered fragments of Siegmund’s sword; foretells the birth of a son, "the highest hero of worlds," to be named Siegfried; and sends Sieglinde to hide herself in the forest to the eastward, where Fafner, the dragon, lies brooding on the hoard, guarding Alberich’s ring. Wotan arrives in hot pursuit of his erring daughter; dismisses her frightened, pleading sisters; and proceeds to tell her what her punishment shall be. She shall be condemned to lie in a magic sleep on the mountain top, and be the bride of the first man who finds and wakens her. This is a scene of exquisite pathos and striking beauty, one of the gems in the colossal drama.

Brünnhilde pleads with her wrathful sire for mitigation of the cruel sentence. Wotan angrily interrupts her, bidding her prepare for her punishment. In despair, she urges that at least she may be guarded, so that none but a hero of valour and determination shall win her. Hesitatingly Wotan yields to her frenzied entreaties. Kissing her fondly to sleep, he summons Loge, the fire-god. Flickering flames immediately burst out, so that Brünnhilde is surrounded with a rampart of fire, through which none but the bravest can pass. Wotan moves away slowly, and the curtains falls. The leave-taking of the Valkyrie and the breaking forth of the flames are illustrated musically by "one of those marvellous effects of graphically decorative writing which prove Wagner’s vocation as a dramatic composer quite as clearly as the higher strains of his tender or passionate imaginings."

Many writers have remarked on the splendour of the character of Brünnhilde. One notes in her the strange commingling of godhood and womanhood. Her sympathy with the doomed pair is, says this acute critic, wholly womanly, and it leads to her becoming entirely a woman when Wotan, in enforcement of the demands of law, kisses the godhead from her. She is a creation as distinct as Shakespeare’s Juliet, as great as Hamlet. In all dramatic literature there is no more majestic female figure than the Brünnhilde of "The Valkyrie" and "Siegfried." In the final drama she diminishes in stature, by reason of the loss of her virginity. Then she is only a weak woman, except in the last scene, when she rises once more on the wings of grief to the proudest heights of self-sacrifice

"The Valkyrie" is, justly, the most generally popular of the four works which constitute "The Ring." The plot is simple and touching, with something of real human interest which readily appeals to the feelings of the listener. Musically, too, the work is generally attractive. There is always a great web of sound being woven, with certain specially brilliant patterns coming to the surface to catch the attention before it has had time to wander. While there are no set "numbers," there are sections that make a similar appeal -- the opening storm, the famous "Ride," the slumber music, and the fire music. On the stage, too, there are striking pictures with effective surprises, as when the door of Hunding’s hut falls open and reveals the forest bathed in moonlight, or when Wotan appears in lightning and storm to interrupt the fight between Siegmund and Hunding, or when the flames shoot up around the sleeping Brünnhilde. "The Valkyrie," like "Siegfried," has colour and variety enough for the amateur who does not care about following the composer’s "guiding themes," and is not at all interested in the underlying philosophic significance of the story.

THE VALKYRIE (DIE WALKURE) POSTER

Brunnhilde - Illustration from "Die Walkure" by Richard Wagner

Size: 18 in x 24 in.

Giclee Print.

Buy at AllPosters.com

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-25 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |