Music with Ease > 19th Century French Opera > Life of Bizet

The Life of Georges Bizet

"Your child is very young," said Meifred, casting a supercilious glance at the little Georges. "That’s true," replied the father, "but if he is small by measurement, he is great in knowledge." "Really! And what can he do?" "Place yourself at the piano, strike chords, and he will name them all without a mistake." The test was applied with success. Other tests followed, and the result was that the doors of the Conservatoire opened to the gifted child out of due time. Bizet’s student career was a series of distinguished triumphs. In 1851, at his first competition, he took second prize for piano, being then only thirteen, and next year he divided the first prize with another. Bizet was, in fact, so good a pianist as to excite (later) the praise of Liszt. Rapidly he rose to the highest place.

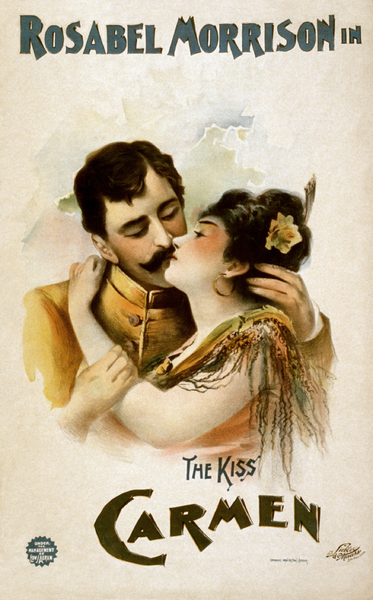

Poster for an American production (c. 1896) of Georges Bizet's most famous opera Carmen, starring Rosabel Morrison as Carmen and under the management of Edward. J. Abraham

By-and-by Offenbach put an opera up to competition, promising to produce the successful work. Bizet tried his luck, and in the result was bracketed at the head of the competition with a classmate, M. Lecocq, whose farcical operas were vastly popular at one time. Bizet went on to better things. He won, like his friend the composer of "Faust," the greatly coveted Prix de Rome at the Conservatoire, and in January 1858 set out for the Eternal City. There he studied hard for three years. Just as he got back to Paris his mother was dying. Under the stress of this bereavement, he settled down to make a living for himself, slaving at arrangements and transcriptions, very much as Wagner had done in that same gay capital. He composed "pot-boilers -- dance movements for orchestra, &c., &c., mean hack drudgery which he detested. "Be assured," he wrote to a friend, "that it is aggravating to interrupt my cherished work for two days to write solos for the cornet-à-pistons. One must live." Again he tells that he is working fifteen or sixteen hours a day; "more sometimes," for he has lessons to give, proofs to correct. Once he says he has not slept for three nights. And yet again: "To be a musician nowadays one needs to have an assured and independent means of living, or genuine diplomatic talent." How true!

He had written an opera (not the first either), "La Jolie Fille de Perth," of which he expected much. It was produced in 1867, ran for twenty-one nights, and then disappeared from the stage, though the ballet music was subsequently incorporated in "Carmen." Two years later, in June 1869, Bizet married Geneviève, the daughter of his old composition master at the Conservatoire, M. Halévy. In 1870 the Franco-German war broke out. Bizet was deeply distressed by this conflict. With the prevision of a seer he wrote: "And our poor philosophy, our dreams of universal peace, our world-wide fraternity, our federation of peoples! Instead of all this, tears, blood, heaps of carcases, crimes without number, without end... This war will cost humanity 500,000 lives. As for France, she will leave all in it. Alas!"

Bizet’s next work was "Djamileh," produced without success in 1872. The composer admitted it was not a success. Nevertheless he said: "I am extremely satisfied with the results obtained. The Press notices have been very interesting, for never has an opéra comique in one Act been more seriously and, let me add, passionately discussed... St. Victor, Jouvain, &c., have been favourable in the sense that they allow inspiration and talent, all spoiled by the influence of Wagner. That which satisfies me more than the opinion of these gentlemen is the absolute certainty that I have hit upon my right course. I know what I am doing."

Then followed the incidental music to Daudet’s play "L’Arlesienne"; music of real merit and beauty, not unknown in the concert room to-day. Daudet’s play was carefully staged but ran only fourteen nights, much to the chagrin of the composer, who "thought he saw once more the condemnation to oblivion of some of his best music." However, M. Pasdeloup, the eminent Parisian conductor, struck by the beauty of the instrumental pieces, performed the Prelude, Minuet, Adagietto, and Carillon, and scored a success with them. The combination became known as a "Suite de Orchestra," and in England it has been generally familiar since Mme. Viard-Louis had it performed at one of her London concerts.

Bizet’s next important effort was the "Patrie" overture, played for the first time at one of Pasdeloup’s concerts, February 15, 1874. Bizet had called the piece simply a "dramatic overture"; Pasdeloup, with an eye to business, and realising that there is more in a name than Juliet was willing to admit, gave it the title by which it is now known. This enlisted national feeling (the war was still remem-bered), and suggested in a single word what was avowedly Bizet’s intention.

And then came "Carmen," by which alone Bizet must surely live. With this masterpiece he had completed his life-work, though he did not know it. The public, as has been told, received it with frigid indifference. But what of that? Bizet had faith in the future of his opera, and he set his face towards other achievements. Alas! he "fell with his foot on the threshold of Walhalla; at the very moment when his star was soaring upwards towards the meridian; just as victory seemed to be within his grasp. On the morning of June 3, 1875, it was whispered through Paris that Bizet had died the previous night. It seemed incredible to his friends that Fate should deal him such a cruel blow.

Confirmation of the report soon came. "Most horrible catastrophe! Our poor friend Bizet died tonight." So ran the telegram. The composer had been stricken suddenly, in his residence at Bougival, and he passed away with little suffering. He had been subject to angina from youth, and the disease became periodic. When it attacked him, he would shut himself in his room, and "quietly await the surcease of his pain, which, as a rule, lasted three or four days." The anxieties and the hard work connected with "Carmen" had proved too much, and May brought an attack of longer duration than usual. At this season of the year Bizet and his family generally left Paris for Bougival. He insisted upon doing so now, despite his illness. "We will go at once," he said; "the air of Paris poisons me." Go he did, and the first day in the country passed off well, the invalid enjoying a walk with his wife and the pianist, Delaborde.

But the following night (Pigot is again the authority) was a horrible one. The poor master, haunted by dreadful visions, oppressed to suffocation, and in pain, could get no repose. The medical man who was hastily summoned did not, however, perceive danger. The same thing happened on the night following. They hesitated to trouble the physician a second time, but the symptoms became more urgent, and at last he was sent for. On his arrival, the patient lay calm and still his wife believed him to be asleep. So he was, but the sleep was that which knows no waking. The hour of midnight sounded when he passed to the Silent Land, and in Paris they were lowering the curtain on the thirty-third representation of the dead man’s masterpiece.

The funeral rites were performed on June 5 at Trinity Church, in presence of four thousand persons. Pasdeloup’s orchestra attended in a body and per-formed the "Patrie" overture; the artists of the Opéra Comique assisted in the Requiem; and Gounod officiated as one of the pall-bearers. There also were Guiraud, Massenet, Delaborde, and a host of repre-sentative men, "sincerely mourning the loss of one whose sun went down while it was yet day." At the close of the religious ceremonies the remains of the composer were laid to rest in the cemetery of Montmartre.

Georges Bizet was thus cut off in the very dawn of his career -- taken early (at thirty-seven), like Mozart and Mendelssohn, like Chopin and Schubert, and our own Purcell. At thirty-seven Verdi had not yet produced "Trovatore"; Wagner was in exile, and "Lohengrin" unappreciated. Had Bizet lived for another thirty years, what might he not have done! As it was, he "achieved little because the opportunity was denied him, but in that little he accomplished much; giving to music the most original and successful opera of his day, and by a single effort earning undying fame."

Pigot tells that some time before his death -- perhaps with a premonition of the end -- Bizet made an auto-da-fe of every MS. which appeared to him short of perfection. He destroyed with pitiless hand all that seemed unworthy to survive; doubtless with injustice to works of incontestable interest and great artistic flavour. Luckily "Carmen" remains.

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-23 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |